Understanding sales cycles – Rodgers, Moore and Christiansen

As said previously, the purpose of ADapT courses is not to teach the details of peripheral techniques used in the method. HOWEVER, some theories and techniques are fundamental building blocks of what we do in ADapT. In these cases, we have to ensure that you have some understanding of the foundational theory used to build the method!

The work of three authors that had a fundamental influence on what we do in ADapT.

The three authors are Everett Rogers, the communication theorist and sociologist, who originated the diffusion of innovations theory.

Secondly, Geoffrey Moore the organisational theorist, management consultant and author who expanded on the works of Rodgers in his classical work Crossing the Chasm (Note: if you read it to make sure you have the latest updated 3rd edition).

And, finally, Clayton Christensen the Harvard academic and business consultant who developed the theory of disruptive innovation. Moore later also developed a strategic framework for dealing with innovation in large publicly listed organisations, called Zoned to Win.

ADapT draws on the work of these three authors to build a strategic innovation decision-making model that we will discuss in board terms at the end of EXTRACT!

To set the scene – a short summary of the work of these authors.

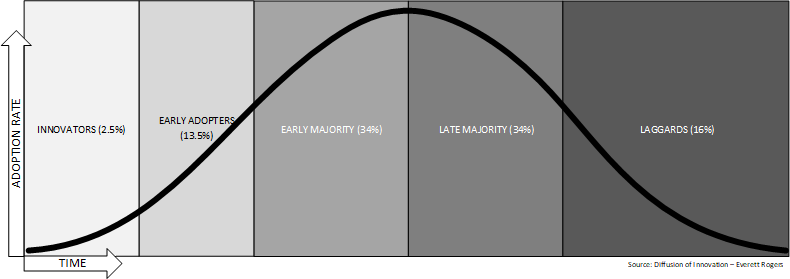

Diffusion of Innovation Theory originated in the field of communication to explain how, over time, an idea or product, let’s call it innovation; spreads (diffuses) through a specific social system and as it does the innovation gains momentum and acceptance. The net result is that people in the social system, adopt a new idea in stages (and groups). Each group has its own set of characteristics, attitudes, behavior, or responses towards the innovation.

There are five categories and stages of adoption, and each stage has a different adopter community. Adoption also follows the classical normal distribution, with the most adopters falling in the middle categories.

If innovators want to communicate (or market) to adopter groups successfully, it is necessary to understand the characteristics of the target group, and different strategies should be used to target different adopter categories.

Innovators – These are people who want to be the first to try the innovation and are willing to take risks. Innovators love ideas because they are innovative and new.

Early Adopters – are opinion leaders. They enjoy a leadership role and embrace opportunities change and improve and know change is important.

The Early Majority – adopt new ideas before the average person, but they do so because they see evidence of the benefits of the innovation, and want those benefits also.

The Late Majority – are sceptics that will only adopt an innovation after it has been tried and tested by the majority.

Laggards – are very conservative. They don’t like change and will resist change until there is no more choice, but to change.

Rodgers also defined a communication strategy with each group, and this is where Moore picked up the strands and developed the next insights.

With the book crossing the chasm, Moore contributed three key insights that changed the way that new (technical and disruptive) innovation is introduced, marketed and sold forever!

Although ostensibly the same categories of potential customers for new innovations have stayed the same, Moore gave them different names to better suit his narrative. He called the categories;

- Technology enthusiasts – say, I want what you have

- Visionaries – say, I believe what you believe (that your product has future benefits)

- Pragmatists – say, I need what you have (because we see that it solves a problem)

- Conservatives – say, we want what they have (because we don’t want to be left behind), and

- Sceptics – say, we will get it because we have to (it’s the only way we can stay compliant with the rest of the world)

Moore then developed a go-to-market playbook for each of three of the categories and two for the pragmatist domain (you will see why later), identifying;

- Who’s the target customer

- Why would they buy your innovation

- What stage of development the product needs to be in

- Is it appropriate to work with partners in selling and installing the product

- What should the sales and distribution strategy be

- How you should determine and handle pricing

- How would competition work

- How you would position yourself and your product, and

- What is the next category/type of customer/s you should target!

Moore realised that many new innovations diffuse only to the second level and fails to reach critical mass. He called this phenomenon ‘the chasm‘.

New innovations fail to cross the chasm for very particular reasons, and if one is aware of that and follow key guidance, that chances of success in innovation are substantial!

The main reason why so many innovations fail to cross the chasm is because Enthusiasts and Visionaries come to the innovator, you basically have to make it known that you have this new innovation – remember they said I believe what you believe and want what you have.

To cross the chasm, organisations need to provide solid proof that their innovation is a solution to a problem the target market has, and the pragmatists want that evidence from one of their own (not the high-tech risk-takers that are enthusiasts and visionaries).

The ONLY way to do that is to find a pragmatist in a niche market with a pain that all the current mainstreet products and services cannot fix. They are desperate for a cure, and that is the ONLY reason why they will give the new innovation a chance.

Innovators then need to dedicate all their efforts and resources to create the cure for the pragmatist in pain so that they can become the evidence other pragmatists are looking for. So in the pragmatist category, there are two playbooks, one for the pragmatist in pain and other people like them, and one for the broader market of pragmatists.

That brings us to Christensen – we had already introduced the work of Christensen earlier when we talked about innovation types (disruptive, sustaining and efficiency) innovation.

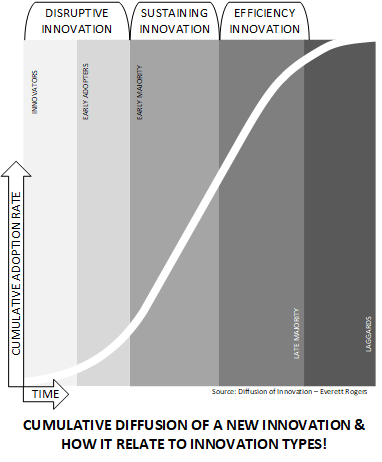

Christensen also identified that the different types of innovation could be mapped to the diffusion of innovation lifecycle. We have already alluded to this insight in the lesson and article that dealt with the organisational immune system.

Disruptive innovation is OK if you are at the beginning of the adoption lifecycle and your customers are enthusiasts and visionaries. Still, pragmatists will not and cannot deal with innovations that are unproven and un-polished. Sustaining innovation is what is required when your primary customers are pragmatists. Once you get to conservatives, you are faced with a declining opportunity, and the only way to make more money out of fewer sales – is to use efficiency innovation.

Moore also echoes this sentiment and has developed additional guidance for each phase and specifically the move from disruptive to sustaining innovation in the book Zone to Win.

If you take the classical diffusion of innovation cycle, and measure, instead of the rate of adoption, measure the cumulative adoption of the innovation, it forms an S curve. Eventually, the curve will flatten, and no new adopters will be found. This S curve is a natural cycle for all products and services, eventually no new customers would buy the product or service.

The time to reach the end of the S curve varies dramatically from product to product and service to service.

We can attempt to lengthen the curve by doing sustaining innovation, and we should!

But Christensen concluded that it would be most prudent to start another innovation cycle before the previous one concludes, and that that is the only way to ensure organisational longevity. It would be best to start thinking about the next wave that will replace your current products and services, the moment you reach the point where the adoption rate starts to decline!

The biggest challenge of that switch is going from operations as usual, back to a state of being disruptive. Its a very challenging transition – and ADapT aims to be your guide throughout the whole cycle.